Our Story: From Hobbyists to Entrepreneurs

“The hermit crab is fishing,” I (Rachel) told my husband, Seth. “That’s crazy. I’ve never heard of such a thing,” he replied. “I’m serious!” I insisted, “He is out on the driftwood catching guppies.”

But, he didn’t believe me - photographic evidence was required. So, I took my little point-and-shoot camera and produced a couple blurry photos of our little guy who had climbed out to the driftwood in the water section of our vivarium and fished for guppies.

The year was 2004 and this was our second vivarium since our marriage two years prior. And, it was the beginning of a joint passion – we just didn’t know it yet.

It’s interesting to look back on your life and see so many things come into focus. We both experienced early love affairs with nature. Seth grew up on a farm with a lot of freedom to roam, catch and release critters he found, and to keep some of his finds as pets. I grew up with a large tract of undeveloped forested land behind our busy suburban home. Those peaceful woods and its tiny creek were my sanctuary. As we journeyed through life, nature connection and natural living became central themes.

Because of our early connection with nature, we found city apartment living stifling. This prompted Seth to start bringing nature indoors with vivariums. The process of determining what kind of environment to create, what animals and plants to select, where to put them, and why was fascinating. When he was done with his first 50-gallon paludarium (a vivarium that is part land and part water), I turned to him and said, “This is amazing. You should make a business out of this.” His reply then: “Oh, I wouldn’t want to make a business out of a hobby.” But, today? He can’t imagine doing anything else.

You see, we had no idea how much that tiny hermit crab would change our lives. Though we had only ever seen hermit crabs in simple, sandy enclosures, we didn’t have enough space for another tank. So we put the little guy in our 50-gallon enclosure. Surprisingly, he loved it! He climbed the ficus tress and pruned them (crazy, but true!). He fished for guppies. He had a good life.

Caption: Our hermit crab in a young ficus tree. He climbed and pruned his trees regularly.(Summer, 2004)

Caption: Our hermit crab in a young ficus tree. He climbed and pruned his trees regularly.(Summer, 2004)

And, all this got us thinking: are hermit crabs really happiest in plain sandy enclosures? Where do hermit crabs live in the wild, anyway? Shouldn’t we better understand how animals live in nature so they can have a better life in captivity?

That was a defining moment. We realized something that seems so obvious now:

In our quest for better living, we added more vivariums and experimented with different layouts, animals, and plants. One of our favorites was a 65-gallon paludarium built in 2005. A planted peninsula was created on the right side, which hid a pump used for water circulation and a built-in waterfall. The water area was full of plants and a couple varieties of fish, including a red and purple male Beta. It was so peaceful to sit and watch the fish, listen to the trickling waterfall, and enjoy the greenery.

Caption: Newly set-up 65g tall paludarium with waterfall (autumn, 2005).

Caption: Newly set-up 65g tall paludarium with waterfall (autumn, 2005).

Caption: Close-up of land section in paludarium with ficus trees and mosses (January, 2006).

Caption: Close-up of land section in paludarium with ficus trees and mosses (January, 2006).

Caption: Close-up of waterfall in 65g tall paludarium (January, 2006) (Note: the brown you see in the water is from the tannins in the cork bark, which was used in the waterfall.)

Caption: Close-up of waterfall in 65g tall paludarium (January, 2006) (Note: the brown you see in the water is from the tannins in the cork bark, which was used in the waterfall.)

As we experimented with different vivariums over the years, we experienced the same problems every hobbyist does if they keep at it long enough: mechanical failures, ecosystem crashes, mold, disease and sometimes death of our animals.

When a mechanical element failed (such as a hidden waterfall pump), it was frustrating to have to tear out a whole landscape to replace it. Not only did this ruin the landscape, plants were often damaged and any animal residents were at increased risk of harm during this process and had to be removed.

We discovered that, despite careful monitoring, ecosystems eventually grew out of balance and “crashed” – which means the ecosystem couldn’t sustain life very well and plants, fish, and other inhabitants would get sick, diseased, and sometimes even die. This happened more frequently in smaller enclosures, such as the 1.5-gallon terrarium below.

Caption: A simplistic, peaceful 1.5-gallon terrarium with DIY hand-crafted background made to look like stone (March, 2009)

Caption: A simplistic, peaceful 1.5-gallon terrarium with DIY hand-crafted background made to look like stone (March, 2009)

Each time something went wrong, we learned and tried again. We experimented with a variety of aquarium sizes, converting them all into terrariums or paludariums. The goal was to increase our connection with nature because nature helped us relax and recharge from our busy lives.

Below is a 5-gallon aquarium that was set up on its short side and converted into a planted terrarium. Seth used a typical DIY method of creating a water-tight glass front with fold-out door and a screen at the top for air exchange. But, even though this method improved air movement, we still experienced challenges with ecosystem balance. Also, we found the black bars and other components visually distracting. While the plants were pretty as they cascaded over the rocks and driftwood, the enclosure itself was not relaxing for me, personally, because of those ugly black bars and screen. It definitely wasn’t something I wanted out in our common living spaces, so it was kept in the basement (with many of our other enclosures).

Caption: 5g aquarium converted to planted terrarium with DIY background, mosses, driftwood, and DIY front designed and built by Seth Hiser in 2009. The HC and mosses grew well, but the black frame and bars were a visual distraction we really disliked.

Caption: 5g aquarium converted to planted terrarium with DIY background, mosses, driftwood, and DIY front designed and built by Seth Hiser in 2009. The HC and mosses grew well, but the black frame and bars were a visual distraction we really disliked.

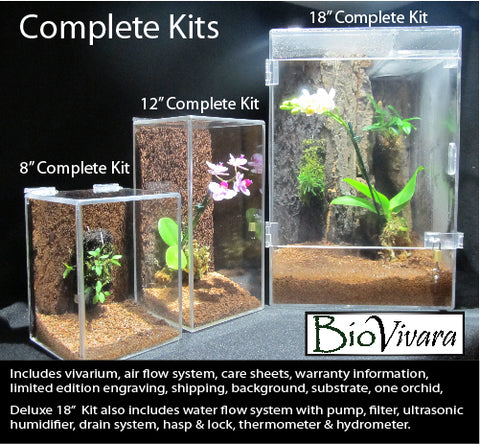

Friends and co-workers started requesting Seth’s help with making DIY backgrounds and even custom enclosures. So, in 2008, we officially launched our business. We named it BioVivara, short for biotope vivaria, because we wanted to focus on designing vivariums that could simulate natural conditions to improve the health of inhabitants and make it easier for busy working parents, like ourselves, to manage. In the first couple years, we focused on using glass aquariums and converting them into terrariums and paludariums, creating backgrounds and designing landscapes.

Caption: Can you find the purple vampire crab in this naturalistic 20g paludarium?

Caption: Can you find the purple vampire crab in this naturalistic 20g paludarium?

Rainforest ecosystems were especially attractive, when well designed. The exotic plants and animals were colorful and interesting. But rainforest biomes are notoriously difficult to recreate because they need both high humidity and high temperature environments. Because of this, it is easy for bad bacteria and unhealthy microorganisms to get out of balance, causing a whole host of problems for the tiny ecosystem. So, we continued to be frustrated with the limitations of market-ready products and DIY options.

Problems with Existing Terrariums

You see, most terrariums were designed for passive air movement and used one or two screens and/or small openings to encourage air flow through the unit. But, that creates a couple problems for a rainforest design. First, it lowers temperature because the unit isn’t adequately sealed or insulated. The DIY solution was to add some sort of heat source (such as a heater underneath the unit or a heat bulb on top).

But, the screen system also lowered relative humidity which meant a constant 100% relative humidity was incredibly difficult to achieve. Some orchids and dart frogs thrive in high humidity and temps of 80+ degrees, so these existing designs had to be modified to trap humidity and insulate the air. But, then the air movement and exchange wasn’t happening so plants and frogs would get sick and sometimes die. The DIY response to this problem was to dangle computer cooling fans in an enclosure to force air circulation. This helped, but was unsightly and potentially dangerous to both plants and animals.

Designing A Better Vivarium

When our pair of Dendrobates tinctorius azureus (a pretty blue and black bodied dart frog) died just a couple years after purchase, we decided we were not getting any more dart frogs until we could make a better vivarium - something that would require less time to manage, offer more control of the environment, and have better long-term stability.

Caption: Our first dart frog enclosure, prior to adding frogs, designed and built DIY fashion reusing our 65-gallon-Tall glass aquarium. The base substrate was built up using plastic eggcrate (a commonly used DIY option to facilitate soil drainage) topped with a combination substrate of cocoa fibers and other organic matter. The rocks were hand sculpted from foam then coated in a stained concrete to look like natural stone. The front area simulated a stream bed with a flood-and-drain system.

Caption: Our first dart frog enclosure, prior to adding frogs, designed and built DIY fashion reusing our 65-gallon-Tall glass aquarium. The base substrate was built up using plastic eggcrate (a commonly used DIY option to facilitate soil drainage) topped with a combination substrate of cocoa fibers and other organic matter. The rocks were hand sculpted from foam then coated in a stained concrete to look like natural stone. The front area simulated a stream bed with a flood-and-drain system.

As we looked at all the options available, we realized that we would have to build what we needed. So, we focused our attention on:

1) Identifying what elements were necessary to make an ideal vivarium,

2) Selecting which materials would be most suitable to create such a vivarium, and

3) Evaluating the best way to make it look good aesthetically

The Research and Development Phase

Once we had our requirements list, we started designing, experimenting and prototyping. Over the course of a couple years and some significant bootstrapping to develop the ideal vivarium, we finally had a model we felt could work. On the advice of a local SBA advisor, we did a soft-launch of our product. So, in May, 2012 we created a Kickstarter project to generate enough pre-sales to help us to buy our first laser-cutter. This laser cutter was an important piece of machinery needed to produce certain components of the design.

Caption: Our prototype product design was offered for pre-sale via Kickstarter, in May, 2012.

Caption: Our prototype product design was offered for pre-sale via Kickstarter, in May, 2012.

Success! We met our goal on Kickstarter with support from around the world.

With our Kickstarter campaign successful, we purchased the laser cutter and got to work filling orders. After working out some kinks, Vivarium Version 1.0 was complete. At that time we called it The Miniature Orchid Desktop Vivarium because it could easily sit on a desk and would allow people to keep miniature orchids (many of which are notoriously hard to keep unless in an adequate enclosure). The larger units (20”x16”x16” and 24”x18”x18”) came to be known as The Rainforest Emulating Vivariums (also sometimes the Nature Emulating Vivariums) because they could consistently recreate the conditions necessary for most biotopes, including the difficult rainforest biotope.

In 2013, we participated in Microcosm in San Diego, meeting some absolutely wonderful people and business owners in the dart frog industry. While there, we also purchased our current oldest resident dart frog (affectionately named Glitch, you can learn about him and the story behind his name in a future blog post) and carefully nurtured him on the long drive back to Ohio.

Caption: Our resident dart frog, Glitch, in his newest habitat built in 2017.

Caption: Our resident dart frog, Glitch, in his newest habitat built in 2017.

R&D continued as we built and sold products, continued testing, made some upgrades, and developed a list of updates we’d like to make for Version 2.0. Then, in 2016, we decided to purchase a larger laser cutter so we could improve the time it took to fulfill orders and improve product quality with our Version 2.0 updates.

Version 2.0 Complete

After hundreds of hours of designing, prototyping, and testing, and another significant investment in materials and equipment, the design updates were complete.

With this update, we decided to rename our product line “The Living Art Vivarium” because we wanted a product name that doesn’t just describe what our product does (re-create sustainable natural environments) but what it is: a beautiful nature-showcase anyone would be proud to display in their home.

Are you ready to create your own Living Art Vivarium? See our enclosure collection in our shop or contact us to talk about your project idea at 877-524-5979 or project@biovivara.com.